1 Introduction

The global number of residential buildings to be constructed is significant, and there is a vast range of structural design requirements. Among all the existing structural types, shear wall structures are one of the most common forms of residential construction. However, its design process involves a considerable amount of repetitive work, resulting in low efficiency and waste of time. Therefore, developing an intelligent design and optimization system for shear wall structures would help enhance design efficiency and elevate the level of intelligence in civil engineering practice.

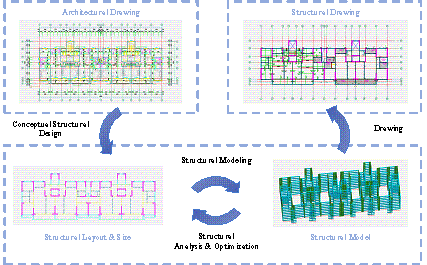

The main design process of shear wall structures typically consists of four phases, including conceptual design, structural modeling, structural optimization, and structural drawing preparation, as shown in Figure 1 [1] . Previous studies have mostly focused on individual phases within the entire process. In relation to conceptual design, recent developments in generative artificial intelligence (AI) have provided new opportunities. Current research utilizes such methods as generative adversarial networks (GANs) [2每6] and graph neural networks (GNNs) [7每9] to automatically and rapidly generate numerous preliminary design schemes for shear wall structures. For rapid structural modeling, tasks such as element recognition and room identification can be accomplished using empirical rules and deep learning methods [10] , enabling the reconstruction of both architectural and structural models [11每15] . For structural analysis and optimization, parametric modeling methods and simplified models have been commonly used to achieve efficient computer-aided design [16] . Specifically, material quantity or cost is optimized as an objective, and the mechanical performance requirements serve as constraint conditions, achieving minimal material consumption while satisfying the given constraints. Although existing methods have demonstrated effectiveness for various specific problems, the integration of structural generation and optimization into a unified system is lacking, and the learning threshold is high, leading to barriers to the practical use of these methods. Issues such as inconsistent data interfaces among different design phases and the lack of guidance from engineers in optimization tasks make the current methods difficult to be comprehensively applied to practical design. Furthermore, it is challenging to simulate real structural design processes and ensure the safety and cost-effectiveness of the design schemes.

Figure 1. Design process of shear wall structures.

The emergence of large language models (LLMs) has introduced new possibilities to address the aforementioned problems [17,18] . LLMs possess strong semantic understanding and content extraction capabilities, enabling the realization of complex functionalities with simple prompts. They can convert various design requirements from structural engineers into executable code and automatically implement method invocations, thereby facilitating the integration of structural generation and optimization methods for shear wall structures. In November 2022, OpenAI [19] released ChatGPT, a natural language processing tool based on an LLM that has reached a professional level of usability in various scenarios, such as interactive dialogues, knowledge retrieval, and translation. Following the wave of AI sparked by ChatGPT, several other research teams have explored different implementation and application domains of LLMs when developing the corresponding chatbots, including Google's Bard [20] , Meta's LLaMA [21] , and Tsinghua University's ChatGLM [22] . However, in these applications, LLMs can only serve as a tool for conversational interactions, making them difficult to be used to solve practical problems. To further explore the application value of LLMs, research teams such as those of AutoGPT [23] and HuggingGPT [24] have begun to build agents with LLM as the core controller to accomplish complex tasks. These agents firstly plan tasks using methods such as the chain of thought [25] or tree of thought [26] , find suitable processing steps, and then correct errors through self-reflection [27] . Finally, they select the appropriate tools or methods for invocation and execution. Li et al. [28] developed benchmarks to evaluate the effectiveness of such agents in responding to human instructions. The same approach has also been applied to robotics [29] . Similarly, in structural design, this approach can also be adopted with an LLM serving as the core controller to realize the entire process of conceptual design, structural optimization, and structural drawing generation through task planning, self-reflection, and method invocation.

Therefore, this study aimed to develop an intelligent design and optimization system for shear wall structures based on LLMs and generative AI. By leveraging robust semantic understanding and content extraction capabilities, an LLM serves as a core controller for an intelligent design and optimization system. Engineers can provide simple prompts on key issues, enabling the LLM to invoke appropriate methods for structural design, adjustment, and optimization. Such a simulation of the design process undertaken by structural engineers maximizes the automation of structural design whilst ensuring the reliability of the design outcomes. In addition, a structural optimization method, taking into account detailed empirical rules, mechanical performance, and material consumption, is proposed for this intelligent design system. By adjusting the optimization objectives and weights through the LLM controller, material consumption can be minimized while satisfying engineers* requirements and mechanical considerations.

This paper presents an intelligent design system for shear wall structures, with specific methods used to implement each component (layer) within the system. Section 2 provides a comprehensive overview of the proposed system and all its layers, and describes the interconnections between various modules used for different design phases, including an LLM controller, structural generation module, and structural optimization module. In Section 3, the specific implementation approach of the structural design core controller based on an LLM is presented. Section 4 introduces the generative design module, and Section 5 discusses the structural optimization module employed by the controller. Section 6 presents a case study to illustrate the effectiveness of the proposed system. Finally, major research findings are summarized in Section 7.

2 System framework

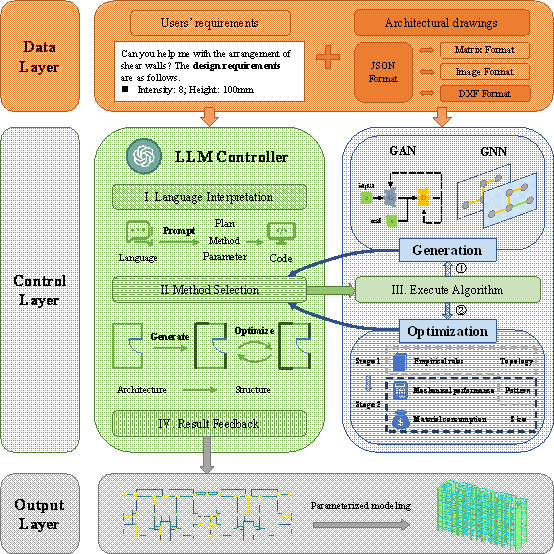

A novel intelligent design system for shear wall structures driven by LLMs and generative AI is proposed herein. As depicted in Figure 2, the overall framework of the system consists of three main components: data, control, and output layers. Specifically, the data layer stores architectural drawings and fundamental data related to structural design. The control layer invokes the relevant algorithms to accomplish the design, adjustment, and optimization tasks for the structure. The output layer presents the final design results for the structure and establishes the corresponding structural analysis model.

The data layer includes two primary types of data. The first type comprises design requirement texts that are directly input into the control layer by users. The second type consists of architectural design drawings that users upload in commonly used CAD file formats. These CAD drawings are subsequently converted into JSON format data using the backend system and are stored in a database, enabling their visual representation and facilitating further processing. Appendix A presents the specific conversion method.

The core of the control layer is the LLM controller, which is inspired by the task-processing approach of HuggingGPT [24] . First, the text describing the design requirements is parsed to plan subsequent tasks and provide the relevant parameters. Subsequently, based on the parsing results, appropriate methods are selected, including structural generation and optimization. The architectural drawings retrieved from the database are then input into the system, where the algorithms are executed to generate the desired design results. During the iterative process of user每controller interaction, the design outcomes can be constantly refined, ultimately leading to an optimized structural design solution that fulfills the specified engineering requirements.

Figure 2. Framework of the intelligent design system for shear wall structures driven by LLMs and generative AI.

The control layer comprises three modules: an LLM controller, structural generation module, and structural optimization module. Generally, for an initial building architectural drawing, the shear wall layout should be generated first, followed by the optimization. It is also possible to generate a new shear wall layout or optimize an existing one as separate tasks. These modules are detailed in Sections 3每5. The core language model in the LLM controller can be selected from various models such as ChatGPT, ChatGLM, and Llama. The algorithm in the structural generation module can be chosen from multiple algorithms, such as GANs and GNNs. Moreover, this study proposes a specialized two-stage optimization method for the structural optimization module. This method allows for individual optimization in Stages 1 and 2 or joint optimization in both stages (Figure 2). Stage 1 optimization represents "topology + pattern" optimization based on empirical rules, while Stage 2 optimization represents "pattern + size" optimization based on mechanical performance and material consumption. The two-stage optimization involves conducting Stage 1 optimization followed by Stage 2 optimization, thereby considering the three levels of topology, pattern, and size to achieve better outcomes. Alternatively, optimization methods similar to those used in other relevant studies can be utilized.

The final design results are represented in the output layer and can be directly converted into CAD drawings. Moreover, it can be transformed into a structural analysis model using parametric modeling methods for subsequent analysis and verification.

3 LLM controller

The implementation of the LLM controller is presented in this section. It is possible to construct an intelligent LLM controller similar to methods such as AutoGPT [23] and HuggingGPT [24] for structural design tasks. This controller can be utilized to manage the generation and optimization of structural designs. By invoking various generation and optimization methods, it can enhance the efficiency of structural design processes.

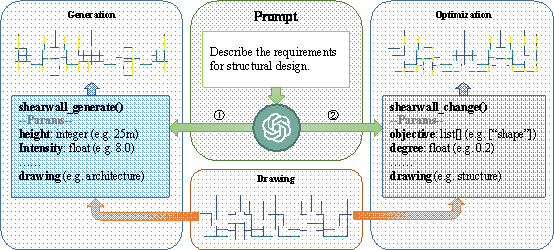

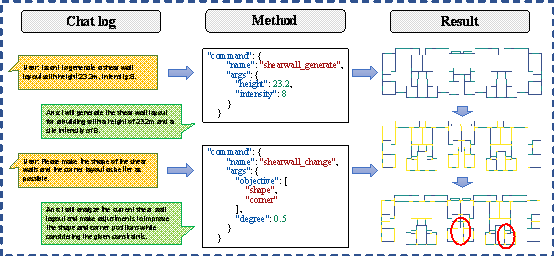

Specifically, algorithms for structural generation and optimization can be integrated to form modular functions. Function names should describe their functionalities, whereas function parameters should match the design and optimization parameters. First, the user inputs are parsed through the LLM controller to determine the task type. For structural generation tasks, the controller firstly parses the user requirements to obtain the corresponding design parameters. For example, the GAN method could be selected for the generation of a structure with a height of 25 m, and is subject to an earthquake with an intensity of 8 degrees (where the corresponding peak ground acceleration for the design basis earthquake exceeding 10% probability in a 50-year design reference period is 0.20 g). Subsequently, the controller simultaneously inputs these textual parameters, draws the files into the function method, and calls the function to generate the desired results, which are then provided as feedback to the user. For structural optimization tasks, the controller is used to parse the user requirements into optimization parameters. For instance, the optimization objective could be the shape of shear walls with an optimization degree of 0.2 (where 80% of the weight in the optimization objective is allocated to maintain consistency with the original design and 20% is allocated to adjustments). The ※topology + pattern§ optimization method of Stage 1 is employed. By inputting textual parameters and drawing files into the function method, the structure can be optimized, and the resulting design improvements can be obtained. The specific implementation is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Methods invoked by the LLM controller.

To ensure effective completion of the aforementioned task using an LLM, a prompt engineering method [30] should be employed. Drawing on inspiration from the implementation of AutoGPT [23] , the LLM is guided through prompts to accomplish a given task. Each function, along with its corresponding name and parameters, is provided to prompt the generation of a JSON-formatted response using the LLM.

The prompt is designed with detailed instructions and constraints, and its specific framework is shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Framework of prompt design.

|

Step |

Prompt |

Instructions and constraints |

|

1 |

Role |

Inform the LLM that it is acting as a structural engineer agent, and its task is to design the structure based on the given architectural layout. |

|

2 |

Goals |

Set goals for the agent, including understanding the user's requirements, selecting appropriate methods for generating or optimizing the structural scheme, and providing suggestions for future structural adjustments. |

|

3 |

Constraints |

Specify the constraints to which the agent must adhere during the thought process. The agent must select the corresponding methods from the provided commands, respond in the English language, and seek assistance from the user when the function parameters are incomplete. |

|

4 |

Commands |

Provide the methods that the agent can execute, including structural generation, structural optimization, and empty commands. This part defines the name of each command along with the meanings and data types of the parameters. |

|

5 |

Resources |

Explain the LLM that the agent utilizes, which in this case is the widely used GPT-3.5. |

|

6 |

Performance Evaluation |

Evaluate the performance of the agent by introducing self-reflection. The agent must review its current actions, consider its role in the overall plan, reflect on past actions, and make better choices regarding command selection and execution. In addition, the agent must verify the function parameters to ensure accurate results. |

|

7 |

Response Format |

Specify the format of the agent's response represented in the JSON format. Each JSON key that represents the thinking process in the response should be explained, and the agent should provide the reasons for taking action, an overall plan, self-critique, and a summary of relevant information, prompting the agent to engage in deeper thinking. |

|

8 |

Notes |

Provide important reminders, such as ensuring that the JSON format can be parsed using Python, the function parameters must be complete, and that the response format must adhere to the aforementioned structure. |

|

9 |

Dialogues |

Finally, store the necessary dialogue history based on previous conversations and add new questions or prompts. |

In accordance with this framework, the actual prompts adopted in this method can be found in Appendix B.

The above prompt and user input are simultaneously input into the LLM, resulting in a JSON-formatted output. Furthermore, the JSON-formatted output is verified and corrected using the LLM to ensure accuracy. The corrected output includes the agent's views and instructions to be executed. By parsing this JSON output using Python, the generation or optimization algorithm is invoked based on the instructions and the corresponding parameters, thereby achieving the appropriate method invocation.

To assess the capability of the agent to handle various user inputs, different questions were selected to test the LLM. The results are summarized in Table 2.

From Table 2, it can be observed that the utilization of the LLM controller facilitates a better comprehension of the engineer's intentions and enables the accurate invocation of specified commands. In cases where the essential parameters are unclear, the agent seeks clarification from the engineer to obtain precise values. Conversely, when the necessary parameters are determined, the agent invokes the corresponding functions based on the parameters, thereby being able to modify and optimize the structure. Moreover, users have the option to manually define the optimization degree by natural language or allow the agent to autonomously set the optimization degree, introducing an element of randomness.

After the implementation of the LLM controller, the corresponding generation and optimization methods can be further investigated, as introduced in Sections 4 and 5, respectively.

Table 2. An interactive case study of LLM controllers.

|

Question |

Response |

Method |

|

What can you do? |

I can help you with generating and optimizing the shear wall layout for your building. Please let me know what specific assistance you need or provide me with more information about your project. |

do_nothing |

|

I want to generate a shear wall layout. |

Sure! Could you please provide the height of the building and the site intensity? |

do_nothing |

|

I want to generate a shear wall layout with height: 40m, intensity: 7. |

I will generate a shear wall layout for a building with a height of 40 meters and a site intensity of 7. |

shearwall_generate(height=40, intensity=7.0) |

|

The shear wall rate* is too low; please adjust the layout. |

To increase the shear wall rate, I suggest evaluating the current layout and identifying areas where additional shear walls can be added. Alternatively, you can consider increasing the length of existing shear walls. |

shearwall_change(objective= [※add_wall§], degree=0.2) |

|

Some shear walls are too short; please adjust the layout. |

I will adjust the shear wall layout to increase the length of the short shear walls. |

shearwall_change(objective= [※min_length§], degree=0.5) |

|

Help me adjust the shape of shear walls and the layout at the corners of rooms. |

I can help you adjust the shape of shear walls and optimize the layout at the corners of rooms. |

shearwall_change(objective= [※shape§, ※corner§], degree=0.5) |

|

Please change the shape of the shear walls with degree:0.1 |

Certainly! To change the shape of the shear walls, I will use the 'shearwall_change' command with the objective set to 'shape' and the degree of adjustment set to 0.1. Is there anything else you would like to modify or any specific suggestions you have in mind to improve the shear wall layout? |

shearwall_change(objective= [※shape§], degree=0.1) |

* The shear wall rate refers to the ratio of the shear wall area to the total floor area.

4 Generation: generative AI-based design

When designing a structure using an LLM controller, the first step involves obtaining an architectural layout plan from the user as a reference. Based on the user input, the initial design of the structural scheme must be performed, which requires the utilization of a structural generation algorithm. Currently, several techniques are available for generating shear wall structure schemes, primarily employing methods such as GANs and GNNs [31] .

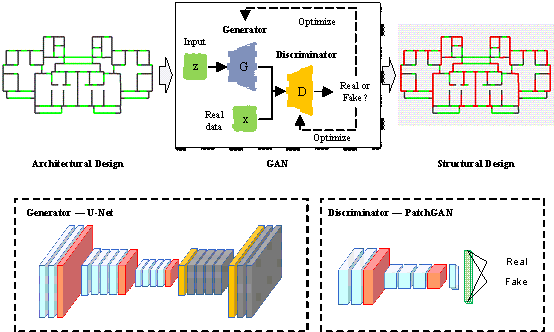

Liao et al. [2] employed a GAN to achieve the intelligent generation of structural schemes by learning from existing design drawings. Approximately 250 pairs of architectural-structural designs from over ten renowned architectural design and research institutes in China were adopted in this study. The drawings were firstly converted into image format, and pix2pixHD model [32] was used for training. The generator employs a U-Net architecture to generate shear wall layouts from random noise, while the discriminator uses a PatchGAN architecture to assess the similarity between the model generated design and that obtained from design engineers, thus achieving image-to-image generation of shear wall layouts. The framework of this approach is illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Method for intelligent design of shear walls based on GAN

Owing to the challenge of representing the relationships between structural components using images in a GAN, Zhao et al. [7,9] introduced a graph edge representation approach for shear wall structures utilizing a GNN with robust capabilities for extracting topological features. In their study, shear wall structure design was successfully accomplished by predicting the attributes of edges. Through a comparative analysis of various feature selections, the study has demonstrated that the design outcomes closely resembled those designed by experienced engineers. The specific implementation method is illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Method for intelligent design of shear walls based on GNN.

Both the GAN and GNN methods demonstrate some advantages. GAN methods exhibit relatively better robustness, whereas GNN methods often yield superior design effects in terms of detail. Qin et al. [33] compared the differences among various algorithms in practical applications. Engineers can select the most appropriate generative method based on the specific requirements and application scenarios. Table 3 provides a detailed comparison of the GAN and GNN methods.

Table 3. Comparison of shear wall layout generation by GAN and GNN

|

Method |

GAN |

GNN |

|

Representation method |

Image |

Graph |

|

Required computational resources |

High |

Low |

|

Model parameter numbers |

High |

Low |

|

Design focus |

Overall structure |

Local topological relationships |

5 Optimization: two-stage optimization based on empirical rule每mechanics每material evaluation

Because the shear wall structure scheme obtained using the generative approach is merely an initial proposal, the LLM controller can further adjust and optimize the scheme of the shear wall based on user requirements.

In existing research on the definition of structural optimization problems, the optimization objectives commonly revolve around material consumption, such as the overall mass or volume of the structure [34,35] and total cost of construction [36每38] . Conversely, the optimization constraints primarily focus on the mechanical metrics of the structure, which encompass overall structural metrics, such as the story drift ratio, period ratio, story stiffness ratio, and rigidity每gravity ratio [34] , as well as component-specific metrics, such as the bending moment, axial force, and shear force of a component [39] .

The optimization methods mentioned above are all single-stage approaches characterized by a large number of parameters. For example, a 6 by 8 grid region results in 2110 potential shear wall layouts [39] , extensive computational time (typically exceeding 10 h), and susceptibility to becoming trapped in local optima. Consequently, there is a pressing need to investigate novel optimization strategies that can effectively balance the quality and efficiency of structural optimization.

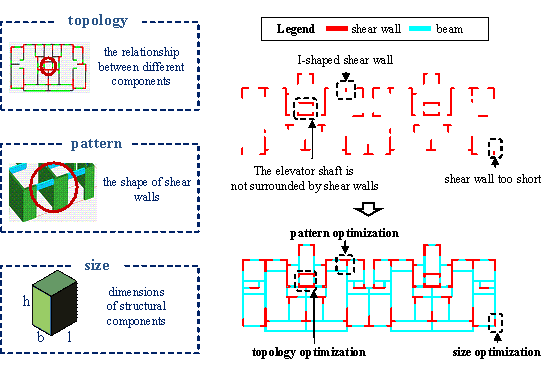

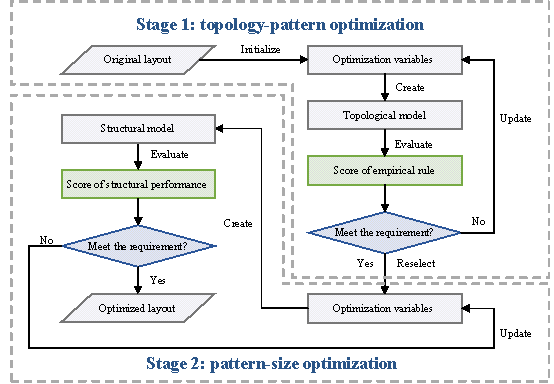

5.1 Two-stage optimization method based on topology, pattern, and size

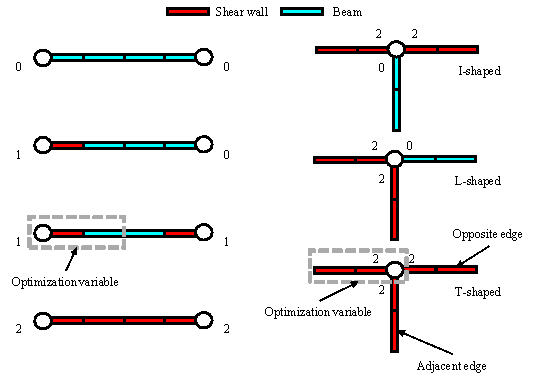

This study proposes a three-level, two-stage optimization method based on topology, pattern, and size to address the characteristics of generation outcomes, as illustrated in Figure 6. The arrangement of structural components with their connections is referred to as topology. Pattern primarily refers to the shape characteristics of a component. The size of a structural component denotes its cross-sectional dimension and length.

Figure 6. Optimization of shear wall structure involves three levels: topology, pattern, and size.

In this optimization method, the initial step involves utilizing the experience and requirements outlined in the structural design specifications to achieve optimization at the topology and pattern levels. This enables the preliminary determination of the structural scheme. Subsequently, adjustments to the pattern and optimization of the component sizes are performed based on precise mechanical and material quantity calculations. This further enhances the structural scheme. The quality and efficiency of the structural optimization are balanced using a two-stage optimization approach, as illustrated in Figure 7.

Figure 7. Flowchart of the two-stage optimization process.

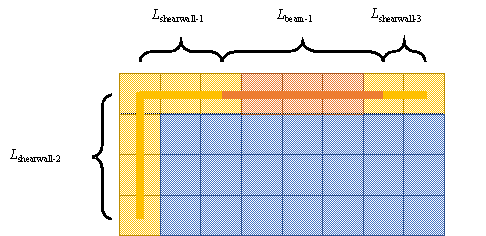

To capture the topology, pattern, and size characteristics

of a structure more effectively, an innovative parametric representation method

is proposed in this study. Previous studies have often employed methods such

as topological graphs [40] and gridization [39] . Topological graphs can express the relationships

between components; however, it is difficult to represent the spatial relationships

between components and rooms, which makes handling component collisions challenging.

Gridization can represent spatial characteristics but is not conducive to

describing the connections between components. This study combines the topological

graphs and gridization methods. As shown in Figure 8, firstly, the components

and space are gridded using the structural design module to set the grid size,

avoiding excessively sparse matrices. Subsequently, the components are identified

and the topological relationships between them are established. This allows

users to take advantage of the strengths of both methods, enabling the rapid

parametric processing of components while also characterizing the relationships

between components and space, thus facilitating the efficient handling of

component collision issues. Note that, in the specific grid representation

method, the actual widths of the components are not considered. Each component

occupies only one grid position in terms of width. The coordinate origin is

located at the center of each grid (Figure 8). For example, ![]() . Because the beam is connected to both ends of the shear walls, it

is necessary to consider the length that overlaps the wall when calculating

the length. In this case,

. Because the beam is connected to both ends of the shear walls, it

is necessary to consider the length that overlaps the wall when calculating

the length. In this case, ![]() .

.

Figure 8. Grid-based representation method for shear wall structures.

5.2 Stage 1: ※topology + pattern§ optimization based on empirical rules

To optimize the topology and pattern based on empirical rules, it is necessary to firstly define the optimization problem, identify the optimization variables, and establish the optimization objectives.

(1) Optimization Variables

This study introduces a universal encoding method, as illustrated in Figure 9, in which the encodings are used as optimization variables. Each node and half of its edges form a point-edge combination, with each combination having three possible encodings: 0, 1, or 2. These encodings represent different relationships. Disregarding the length of the wall, this representation method accurately captures various structural topology relationships and component patterns.

Figure 9. Encoding method for node每edge combinations

Furthermore, considering the global and local symmetries present in an actual structural layout, certain node每edge combinations can exhibit identical layout characteristics and can be merged. Therefore, the k-means algorithm [41] is introduced to achieve clustering.

To achieve more accurate clustering, feature extraction is performed on the node每edge combinations, considering their intrinsic properties and positional relationships. These features are divided into six categories, as listed in Table 4.

The features are standardized, and the clustering process of node每edge combinations is performed using the Calinski每Harbasz score [42] to select an appropriate value for K. Each class is represented by the same encoding as an optimization variable, significantly reducing the number of optimization variables and ensuring both the efficiency of optimization and the symmetry of the results.

Table 4. Feature extraction of node每edge combinations

|

Index |

Feature |

Encoding rule |

|

1 |

Direction of the edge. |

The x-direction is 0, whereas the y-direction is 1. |

|

2 |

Corresponding length of the edge. |

The corresponding number of grid cells. |

|

3 |

Number of edges |

The components are connected orthogonally, so the value ranges from 1 to 4. |

|

4 |

Length of the opposite edge. |

If there is an opposite edge (as shown in Figure 9), the number of grid cells corresponding to the opposite edge is considered; otherwise, it is 0. |

|

5 |

Maximum value of adjacent edges. |

If there are adjacent edges (as shown in Figure 9), the length is determined by the number of grid cells along the adjacent edges; otherwise, it is 0. Then, the maximum and minimum values are calculated, respectively. |

|

6 |

Minimum value of adjacent edges. |

(2) Optimization objectives

When determining the optimization objectives, the initial value of the initial scheme should be considered. The similarity between the optimized and initial schemes is introduced as part of the optimization objective. The optimization intensity is adjusted by controlling the weight of similarity.

To evaluate the similarity between the optimized and initial schemes, we employ the commonly used intersection over union (IoU) [43] metric for target detection. IoU is defined as the intersection of two sets, A and B, divided by their union, as shown in Equation (1).

![]()

In addition, it is possible to establish a set of empirical rule metrics to indicate the direction of optimization. The empirical rule metrics for the structural layout include the shear wall shape, corner support, and wall ratio. The calculation methods for shear wall shape metrics and corner support metrics are introduced in Section 6 Case study. For a detailed definition of the optimization metrics, please refer to Qin et al. [44] . Moreover, the entropy weight method [45] can be used to determine the weight of each metric and comprehensively evaluate the results.

The ultimate optimization objective can be obtained by summing up the aforementioned multiple metrics with specified weighting based on the actual requirements. A corresponding case study is presented in Section 6.

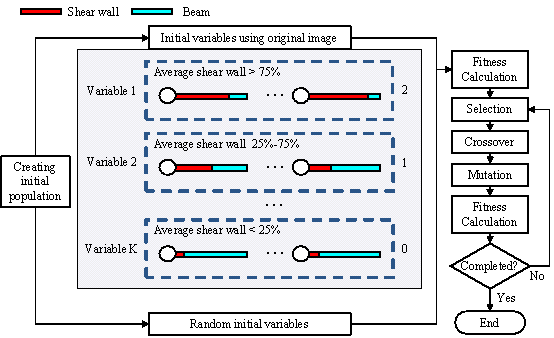

(3) Algorithm Implementation

Owing to the discrete nature of the optimization variables,

a widely applicable genetic algorithm (GA) [46] was adopted for optimization. The strengthened elitist GA algorithm

[47] is employed to enhance the optimization performance. To ensure that

the generated results align with the requirements of practical structural

design, the values of each variable are initialized based on the initial structural

scheme. Using the k-means algorithm, each variable is composed of multiple

node每edge combinations. Let ![]() represent the ratio between the length of the shear wall

already arranged and the total length of the node每edge combination for each

variable

represent the ratio between the length of the shear wall

already arranged and the total length of the node每edge combination for each

variable ![]() and node每edge combination

and node每edge combination ![]() . Therefore, the initial value

. Therefore, the initial value ![]() of the variable can be calculated using Equation (2).

of the variable can be calculated using Equation (2).

![]()

The closest initial variable representation to the original image can be obtained using this method. A subset of the initial population is selected as the initial variable value to enhance the efficiency of the optimization process. The specific operational process of the genetic algorithm is shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10. Flowchart of the genetic algorithm in ※topology + pattern§ optimization

5.3 Stage 2: ※pattern + size§ optimization based on mechanical performance and material consumption

After determining the topological layout of the structure, ※pattern + size§ optimization can be implemented.

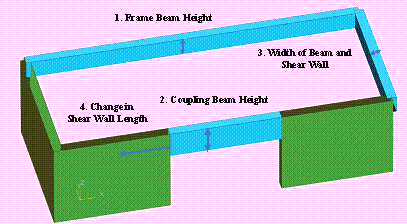

(1) Optimization Variables

The optimization variables include the beam height, beam width (which is usually equal to the wall width), and wall length. Because of the excessive computational cost of individually optimizing the dimensions of each component, this section provides simplified approaches for selecting certain variables based on design experience. The specific variable choices are shown in Figure 11.

Figure 11. Variable selection in Stage 2.

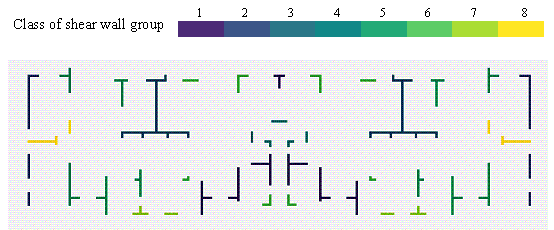

The frame beam height, coupling beam height, and beam width are merged separately and represented by individual variables. However, because of the significant differences in the wall group characteristics, it is challenging to reflect the change in the shear wall length with a single variable. To address this issue, the k-means algorithm is employed to classify wall groups and reduce the number of variables. The specific feature extraction process is presented in Table 5, which encompasses essential information such as wall shape and position, enabling the effective differentiation of wall groups.

Table 5. Feature extraction of shear wall groups.

|

Index |

Feature |

|

1 |

The number of nodes connected to only one edge |

|

2 |

The number of nodes connected to two edges |

|

3 |

The number of nodes connected to three edges |

|

4 |

Total length of wall groups |

|

5 |

Average distance from the x-coordinate of nodes to the center |

|

6 |

Average distance from the y-coordinate of nodes to the center |

(2) Optimization objectives

To quantitatively evaluate the mechanical performance and material consumption of a structure, a penalty function can be constructed based on the mechanical constraints. This enables the definition of an evaluation score as a new objective function, where a smaller score indicates a better structure. Based on the experience of engineers, the selected mechanical constraints included the story drift ratio, wall axial compression ratio, and beam shear compression ratio (the ratio between the average shear stress on the cross-section and the design value of the axial compressive strength of concrete) [44] .

A penalty function for the story drift ratio is formulated

as Equation (3), where ![]() represents the maximum story drift ratio, and

represents the maximum story drift ratio, and ![]() denotes the limit of the story drift ratio. Considering

the requirement of meeting the limit of the story drift ratio in practical

engineering, it is advisable to set the benchmark at 0.9 times the limit of

the story drift ratio to reserve a certain margin. This approach ensures that

the story drift ratio values are close to this benchmark, as suggested by

experienced engineers.

denotes the limit of the story drift ratio. Considering

the requirement of meeting the limit of the story drift ratio in practical

engineering, it is advisable to set the benchmark at 0.9 times the limit of

the story drift ratio to reserve a certain margin. This approach ensures that

the story drift ratio values are close to this benchmark, as suggested by

experienced engineers.

![]()

The axial compression ratio penalty function is constructed

using Equation (4), where ![]() represents the axial compression ratio of each wall component

in the first layer,

represents the axial compression ratio of each wall component

in the first layer, ![]() is the limit of the axial compression ratio for that component,

and

is the limit of the axial compression ratio for that component,

and ![]() denotes the average value across all the walls. As the

ground story has the highest axial compression ratio, it is sufficient to

ensure that the axial compression ratio of the ground story satisfies this

limit. Using a benchmark of 0.9 times the limit value, the penalty function

can be obtained by calculating the average score for each wall group.

denotes the average value across all the walls. As the

ground story has the highest axial compression ratio, it is sufficient to

ensure that the axial compression ratio of the ground story satisfies this

limit. Using a benchmark of 0.9 times the limit value, the penalty function

can be obtained by calculating the average score for each wall group.

![]()

The penalty function for the shear compression ratio is

formulated in Equation (5), where ![]() represents the shear compression ratio for each beam component,

represents the shear compression ratio for each beam component,

![]() is the specified limit for the shear compression ratio

of that component, and

is the specified limit for the shear compression ratio

of that component, and ![]() denotes the number of beam components. Because the impact

of exceeding the shear compression ratio limit on the results is relatively

minor, a penalty function can be designed based on the proportion of beam

components that has exceeded the limit.

denotes the number of beam components. Because the impact

of exceeding the shear compression ratio limit on the results is relatively

minor, a penalty function can be designed based on the proportion of beam

components that has exceeded the limit.

![]()

The ultimate optimization objective, denoted as

![]() , is the sum of the total material cost

, is the sum of the total material cost ![]() and the penalty term. To satisfy the constraints as much

as possible, the penalty factor is also selected as the total material cost

and the penalty term. To satisfy the constraints as much

as possible, the penalty factor is also selected as the total material cost

![]() . The material cost is calculated based on the market prices of concrete

(300 CNY/m3; 1 CNY = 0.14 USD as of Oct. 24, 2023) and steel

reinforcement (4000 CNY/t). The final optimization objective is given by Equation

(6).

. The material cost is calculated based on the market prices of concrete

(300 CNY/m3; 1 CNY = 0.14 USD as of Oct. 24, 2023) and steel

reinforcement (4000 CNY/t). The final optimization objective is given by Equation

(6).

![]()

(3) Algorithm Implementation

Based on the optimization variables mentioned earlier, parametric modeling of the shear wall structure can be performed using the GAMA module of the YJK V5.2.1 structural modeling and analysis software [48] . This allows for efficient calculation and analysis of structural performance, determination of key structural metrics, and estimation of material consumption. The final results are obtained through iterative optimization, while concurrently establishing the final structural model.

6 Case study

6.1 Basic information

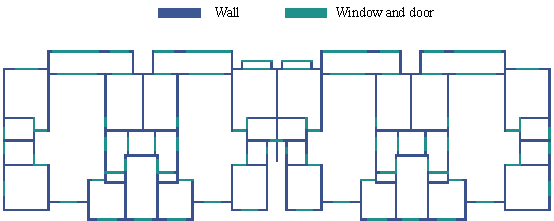

The case study relates to a shear wall structure building consisting of eight stories, each with a height of 2900 mm and a floor area of 552 m2. The seismic intensity was set to 8 degrees. The characteristic period at the site is 0.4 s. The building layout is shown in Figure 12. The line load on the beam is set as 3.6 kN/m. The thickness of the slab is 120 mm. The live and dead loads on the slab are 2 kN/m2 and 5 kN/m2, respectively.

Figure 12. Architectural layout of the case study building.

6.2 Structural scheme generation and optimization under LLM Control

The ChatGPT model was used as the controller in this case study. The generation algorithm employed was StructGAN [2] , whereas the optimization algorithm followed the two-stage method outlined in Section 5. The specific prompts are presented in Appendix B. A JSON-format document containing feedback from the back end can be found in Appendix C. The question每answer results and adjustments made to the shear wall structure in a two-round dialogue are shown in Figure 13.

Figure 13. Intelligent design system for the case study shear wall structure.

6.2.1 Generation

From Figure 13, it can be observed that the first-round dialogue invoked the function of structural generation, namely ※shearwall_generate (height=23.2, intensity=8.0)§. This function adopted the drawing and parameters derived from the LLM analysis as inputs. By employing a generative design approach, a preliminary scheme for the shear walls was developed. The scheme was then provided as feedback to the engineer, who subsequently proposed further modifications based on the structural layout.

6.2.2 Optimization

The second-round dialogue involved selecting appropriate

optimization targets based on the engineer's modification requirements. First,

the shear wall layout was adjusted using the Stage 1 optimization method.

Specifically, the function called was ※shearwall_change(objective=["shape",

"corner"], degree=0.5)§. The ※objective§ indicated that

the optimization objectives were the shapes of the shear walls and the support

of corner points. The ※degree§ was set to 0.5, representing the combined

weight of the two metrics in the optimization objective, while the remaining

weight of 0.5 was allocated to the ![]() metric.

metric.

(1) Stage 1

The optimization objectives, in this case, included

![]() , the shear wall shape index

, the shear wall shape index ![]() , and the corner support index

, and the corner support index ![]() . Based on the parameter ※degree§ in the LLM invocation, a weight

of 0.5 was assigned to IoU. Furthermore, weights were allocated to

the shear wall shape and corner support objectives using the entropy weight

method [44,45] . Finally, the optimized objective function can be expressed by Equation

(7)每(10).

. Based on the parameter ※degree§ in the LLM invocation, a weight

of 0.5 was assigned to IoU. Furthermore, weights were allocated to

the shear wall shape and corner support objectives using the entropy weight

method [44,45] . Finally, the optimized objective function can be expressed by Equation

(7)每(10).

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Optimization was performed using a strengthen elitist GA

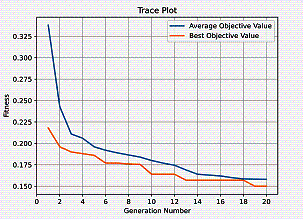

algorithm in Python geatpy library [49] based on the optimization objective ![]() . The specific parameters of Stage1 are referenced in Table 6. The

optimization process in this stage is illustrated in Figure 14, which shows

a rapid convergence speed. The total time for Stage 1 was 459 s. Subsequently,

this result was utilized for further optimization in Stage 2 to determine

the pattern and size of the structure.

. The specific parameters of Stage1 are referenced in Table 6. The

optimization process in this stage is illustrated in Figure 14, which shows

a rapid convergence speed. The total time for Stage 1 was 459 s. Subsequently,

this result was utilized for further optimization in Stage 2 to determine

the pattern and size of the structure.

Table 6. Parameters of Stage 1

|

Parameter |

Value |

Description |

|

K |

〞 |

Determined based on the Calinski and Harabasz score [42] of k-means |

|

Crossover |

〞 |

Two-point Crossover |

|

Mutation |

〞 |

Mutation of Breeder Genetic Algorithm [50] |

|

Population |

50 |

The number of individuals in the population |

|

XOVR |

0.7 |

The probability of crossover occurring |

|

Pm |

1/K |

The probability of mutation occurring in the smallest segment affected by the mutation operator on the chromosome |

|

MutShrink |

0.5 |

Compression rate, used to limit the range of mutation |

|

Gradient |

20 |

The number of gradient divisions for mutation distance |

Figure 14. Optimization curve for Stage 1.

(2) Stage 2

First, the shear wall groups were clustered using the k-means algorithm. To prevent optimization difficulties due to the large number of variables, the value of K in the k-means algorithm should not be excessively large. In this case, we selected K = 8 for Stage 2 optimization. The clustering results for the shear wall groups are presented in Figure 15. Note that the shear wall groups were divided into 8 classes based on their shapes, lengths, and locations.

Figure 15. Results of shear wall clustering based on k-means algorithm.

The ranges and steps of each optimization variable are presented in Table 7, based on the optimization variables selected in Stage 2 of Section 5.3.

Table 7. Range of optimization variable values.

|

Variable |

Range (mm) |

Step (mm) |

|

Frame beam height |

400 ~ 600 |

50 |

|

Coupling beam height |

400 ~ 600 |

50 |

|

Beam width (wall width) |

200 ~ 300 |

50 |

|

Change of shear wall length (Class 1-8) |

-200 ~ 200 |

200 |

The optimization process was conducted using an online learning method provided by YJK-GAMA. The total duration of Stage 2 was 59 min, and the resulting values for each variable after optimization are presented in Table 8.

Table 8. Variable values after optimization in Stage 2.

|

Variable |

Value (mm) |

|

Frame beam height |

400 |

|

Coupling beam height |

400 |

|

Beam width (wall width) |

200 |

|

Change of shear wall length 1 |

0 |

|

Change of shear wall length 2 |

0 |

|

Change of shear wall length 3 |

200 |

|

Change of shear wall length 4 |

200 |

|

Change of shear wall length 5 |

200 |

|

Change of shear wall length 6 |

-200 |

|

Change of shear wall length 7 |

-200 |

|

Change of shear wall length 8 |

-200 |

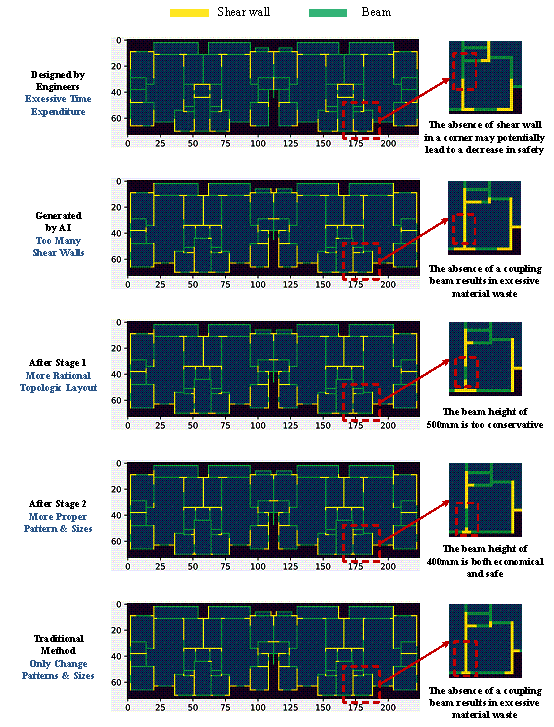

By comparing the evaluation scores and drawings of each stage with the engineer's design and the traditional method of direct optimization, the results were obtained, as presented in Tables 9, 10, and Figure 16.

Table 9. Evaluation results of empirical rules.

|

Design scenario |

|

|

|

Designed by engineers |

0.83 |

0.86 |

|

Generated by AI |

0.45 |

1.00 |

|

After Stage 1 |

0.82 |

1.00 |

|

After Stage 2 |

0.79 |

1.00 |

|

Traditional method |

0.42 |

1.00 |

Table 10. Evaluation results of mechanical performance and material consumption.

|

Design scenario |

Steel reinforcement consumption (t) |

Concrete consumption (m3) |

Total material cost (k CNY) |

Maximum story drift ratio |

|

Designed by engineers |

129.74 |

1203.28 |

879.94 |

1/1269 |

|

Generated by AI |

126.73 |

1395.22 |

925.49 |

1/1908 |

|

After Stage 1 |

124.29 |

1269.42 |

877.99 |

1/1596 |

|

After Stage 2 |

119.25 |

1186.32 |

832.90 |

1/1237 |

|

Traditional method |

121.20 |

1313.26 |

878.78 |

1/1414 |

Figure 16. Comparison of structural schemes by different design scenarios.

The results indicate that in Stage 1, significant optimization in the layout pattern of the shear walls was performed, resulting in an increase in the number of L-shaped and T-shaped walls and a preliminary reduction in material consumption. Further, Stage 2 optimization focused on specific dimensions, leading to a further decrease in material consumption. Compared to the traditional direct optimization method, both the empirical and the mechanical performance每material consumption evaluation methods showed notable improvements. The total material cost was reduced by 45.88 k CNY compared to the traditional method. Additionally, the empirical evaluation and mechanical performance results were similar to those obtained by design engineers, whereas the overall material cost decreased by approximately 47.04 k CNY.

Finally, a time comparison was made on typical design scenarios. Based on the research conducted by senior engineers from several top design institutes in China [51] , the design process for a shear wall structure with an approximate floor area of 500 m2 requires approximately 20 h for preliminary design and 10 h for structural modeling. Furthermore, a significant amount of time is often spent on subsequent adjustments and optimization after the preliminary design. In contrast, the total time required by the proposed intelligent design system was about 1 h, resulting in an efficiency improvement of approximately 30 times. The time required for completing this design case are compared in Table 11. Moreover, the system can be implemented using natural language dialogues, which significantly reduces the learning threshold.

Table 11. Comparison of design efficiency between different methods

|

Designer |

Preprocess |

Design |

Model |

Optimization |

Total |

Time difference |

|

Engineer (manually) |

0 h |

20 h |

10 h |

5 h |

35 h |

28.77 |

|

Design system |

5 min |

1 min |

0 min |

67 min |

73 min |

7 Conclusion

This paper proposes an intelligent design system for shear wall structures based on LLMs and generative AI. By incorporating simple interactions, an efficient structural design is achieved, and the automation and convenience of the shear wall design process are significantly enhanced. The system utilizes an LLM as the core controller, which translates the design and optimization requirements expressed in natural language into computer-executable code. It manipulates generative AI algorithms to generate the initial layout, and controls the optimization objectives to further adjust the structure details. Through iterative interactions, the final results are obtained, providing valuable references for future development of generic intelligent design systems. Major conclusions are as follows:

(1) The proposed intelligent design system for shear wall structures based on LLMs and generative AI integrates structural generation and optimization methods. The LLM serves as the core of interactive control, enabling the automated completion of the entire structural design process in an interactive fashion. This approach not only ensures safety and cost-effectiveness of a design outcome, but also improves the design efficiency by approximately 30 times.

(2) In this study, a two-stage optimization method based on empirical rules, mechanical performance, and material consumption was proposed for the entire process of AI intelligent generation and optimization. This method significantly reduces the material consumption while ensuring that the structure meets the mechanical constraints, thereby improving the optimization efficiency.

(3) A reasonable and domain-knowledge-inclusive prompt was designed for the LLM in the field of structural design. The effective implementation of the LLM method based on natural language dialogue for controlling the structural design significantly reduces the difficulty sof using the proposed intelligent design system.

In the future, it will be possible to utilize advanced pretraining LLM techniques to achieve a profound comprehension and application of knowledge in the field of structural design. Furthermore, there is potential to introduce an additional agent to review the methods invoked by the LLM controller and the generated outcomes, thereby simulating the design review process in practical settings and enhancing the accuracy of the final design.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Sizhong Qin: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing 每 original draft, Writing 每 review & editing. Hong Guan: Resources, Supervision, Writing 每 review & editing. Wenjie Liao: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Resources, Supervision, Writing 每 original draft, Writing 每 review & editing, Yi Gu: Data curation, Software, Validation, Visualization. Zhe Zheng: Formal analysis, Software, Validation, Writing 每 original draft. Hongjing Xue: Data curation, Investigation, Resources. Xinzheng Lu: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Resources, Supervision, Writing 每 review & editing

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgment

Appendix A

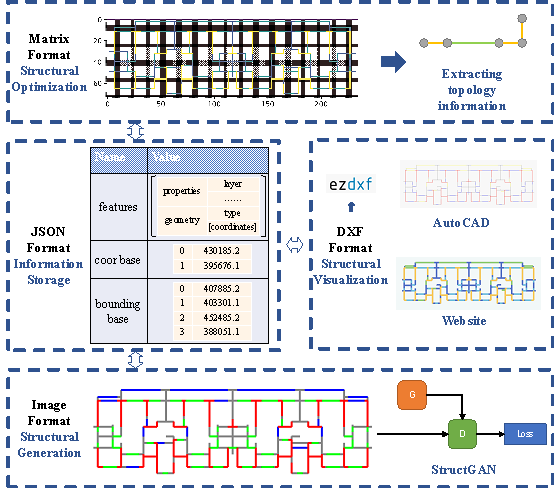

Owing to the incorporation of various functionalities such as information storage, structural generation, structural optimization, and structural visualization, the development of each functionality relies heavily on the representation format of the data. To align the data format with its corresponding functionality, we constructed four distinct formats to express the structural information. These formats are applied to different functional scenarios, and the conversion relationships among the four formats are shown in Figure A.1.

Figure A.1. Four different formats of expressing structural information (coor refers to coordinate).

The JSON-format data are stored in the database as the benchmark data format, allowing for bidirectional conversion to other formats. JSON stores the coordinates and layer properties of structural components, boundary coordinates of structural drawings, and base-point coordinates, enabling the representation of the vast majority of architectural and structural drawings. By adopting this approach, which provides an accurate coordinate expression and easy storage management, the use of JSON as the benchmark data format ensures data accuracy and minimizes redundancy in the database.

A widely used approach for structural generation is to utilize a GAN [2] . This method requires input files in the image format for generation, and the generated results are also presented in the image format. This study implemented a bidirectional conversion process between image and JSON formats using the OpenCV library and relevant methods in computer graphics, facilitating subsequent design and optimization tasks.

Detailed parametric modeling method in structural optimization is given in Section 5.1.

Two distinct approaches have been implemented in the domain of structural visualization to cater to diverse user requirements. The adoption of the DXF file format allows for editing and adjustments within professional drawing software such as AutoCAD. In addition, web-based interactive visualization can be achieved by utilizing the ezdxf library.

Appendix B

A reference prompt for the LLM is provided below, which currently includes only a selection of functions.

You are a Civil Engineer.

The available information regarding the building layout provides a foundation for the design of the structure.

### Goals:

1. Parse the input to understand users' requirements.

2. Choose proper commands to generate or optimize the shear wall layout.

3. Give some suggestions to make the shear wall layout better.

### Constraints:

1. Exclusively use the commands listed in double quotes e.g. "command name".

2. User will talk with you in any language, but you ONLY need to reply in English.

3. **If you are not sure about some args in the commands, choose the command "do_nothing" and ask user for help.**

### Commands:

1. Generate shear wall: "shearwall_generate", args: "height": "<the_height_of_the_building type: integer>", "intensity": "<the_site_intensity_of_the_building type: float>"

2. Adjust shear wall: "shearwall_change", args:

"objective": "<which_objective_to_adjust_the_layout type:

list[string] choice:

"shape"(It would be better to make the shape of the shear wall groups more proper),

"corner"(It would be better to ensure the corners of each room supported by shear wall),

"add_wall"(The shear wall ratio is too low. It would be better to increase the number or length of shear walls),

"reduce_wall"(The shear wall ratio is too high. It would be better to decrease the number or length of shear walls),

"max_length"(The length of a piece of shear wall should not be too long),

"min_length"(The length of a piece of shear wall should not be too short)>,

"degree":"<how_much_ajustment_is_made type: float from 0 to 0.5>"

3. Do Nothing: "do_nothing", args:

### Resources:

1. GPT-3.5 powered Agents for delegation of simple tasks.

### Performance Evaluation:

1. Continuously review and analyze your actions to ensure you are performing to the best of your abilities.

2. Constructively self-criticize your big-picture behavior constantly.

3. Reflect on past decisions and strategies to refine your approach.

4. Check the args of the command and ensure that all parameters are substantiated.

You should only respond in JSON format as described below:

### Response Format:

{

"thoughts": {

"text": "thought",

"reasoning": "reasoning",

"plan": "short bulleted list that conveys long-term plan",

"criticism": "constructive self-criticism",

"speak": "thoughts summary to say to user"

},

"command": {

"name": "command name",

"args": {

"arg name": "value"

}

}

}

### Notes

**Ensure the response can be parsed by Python json.loads.**

**Ensure the args of the command is complete.**

**Determine which next command to use, and respond using the format specified above:**

### Dialog

Appendix C

The JSON representations of the two problem instances in Section 6 are as follows.

{

"thoughts": {

"text": "The user wants to generate a shear wall layout with a building height of 23.2m and a site intensity of 8. I should proceed with the 'shearwall_generate' command to generate the layout.",

"reasoning": "The 'shearwall_generate' command is appropriate for generating the shear wall layout based on the specified height and intensity.",

"plan": "- Execute 'shearwall_generate' command with the given arguments.\n- Generate the shear wall layout.",

"criticism": "No criticism to address.",

"speak": "I will generate the shear wall layout for a building with a height of 23.2m and a site intensity of 8."

},

"command": {

"name": "shearwall_generate",

"args": {

"height": 23.2,

"intensity": 8

}

}

}

{

"thoughts": {

"text": "The user wants to generate a shear wall layout for a building with a height of 23.2m and a site intensity of 8. They also want to improve the shape of the shear walls and the corner layout. I can adjust the shear wall layout to meet their requirements.",

"reasoning": "To improve the layout, I can adjust the shape and corner positions of the shear walls. I'll need to come up with a plan to optimize these aspects while considering the given constraints.",

"plan": "- Analyze the current shear wall layout.\n- Identify areas where the shape and corner layout can be improved.\n- Generate a modified layout that optimizes the shape and corner positions.\n- Evaluate the modified layout against the given constraints.\n- If the modified layout is satisfactory, present it to the user. Otherwise, make further adjustments.\n- Repeat the process until an optimal layout is achieved.",

"criticism": "I need to be careful with the adjustments I make to the layout. While trying to improve the shape and corner layout, I should ensure that the shear walls still provide adequate structural support and comply with the necessary design standards.",

"speak": "I will analyze the current shear wall layout and make adjustments to improve the shape and corner positions while considering the given constraints."

},

"command": {

"name": "shearwall_change",

"args": {

"objective": [

"shape",

"corner"

],

"degree": 0.5

}

}

}

Reference

[1] H.-L. Chi, X.Y. Wang, Y. Jiao, BIM-enabled structural design: Impacts and future developments in structural modelling, analysis and optimisation processes, Arch Computat Methods Eng 22 (2015) 135每151. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11831-014-9127-7.

[2] W.J. Liao, X.Z. Lu, Y.L. Huang, Z. Zheng, Y.Q. Lin, Automated structural design of shear wall residential buildings using generative adversarial networks, Automation in Construction 132 (2021) 103931. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2021.103931.

[3] W.J. Liao, Y.L. Huang, Z. Zheng, X.Z. Lu, Intelligent generative structural design method for shear wall building based on ※fused-text-image-to-image§ generative adversarial networks, Expert Systems with Applications 210 (2022) 118530. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2022.118530.

[4] X.Z. Lu, W.J. Liao, Y. Zhang, Y.L. Huang, Intelligent structural design of shear wall residence using physics坼enhanced generative adversarial networks, Earthq Engng Struct Dyn 51 (2022) 1657每1676. https://doi.org/10.1002/eqe.3632.

[5] P.J. Zhao, W.J. Liao, Y.L. Huang, X.Z. Lu, Intelligent design of shear wall layout based on attention-enhanced generative adversarial network, Engineering Structures 274 (2023) 115170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engstruct.2022.115170.

[6] Y.T. Feng, Y.F. Fei, Y.Q. Lin, W.J. Liao, X.Z. Lu, Intelligent generative design for shear wall cross-sectional size using rule-embedded generative adversarial network, Journal of Structural Engineering 149 (2023) 04023161. https://doi.org/10.1061/JSENDH.STENG-12206.

[7] P.J. Zhao, W.J. Liao, Y.L. Huang, X.Z. Lu, Intelligent design of shear wall layout based on graph neural networks, Advanced Engineering Informatics 55 (2023) 101886. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aei.2023.101886.

[8] P.J. Zhao, W.J. Liao, H.J. Xue, X.Z. Lu, Intelligent design method for beam and slab of shear wall structure based on deep learning, Journal of Building Engineering 57 (2022) 104838. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2022.104838.

[9] P. Zhao, Y. Fei, Y. Huang, Y. Feng, W. Liao, X. Lu, Design-condition-informed shear wall layout design based on graph neural networks, Advanced Engineering Informatics 58 (2023) 102190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aei.2023.102190.

[10] P.N. Pizarro, N. Hitschfeld, I. Sipiran, J.M. Saavedra, Automatic floor plan analysis and recognition, Automation in Construction 140 (2022) 104348. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2022.104348.

[11] X.H. Zhou, X.S. Huang, J.P. Liu, G.Z. Cheng, L.F. Wang, J.H. Hu, P.K. Liu, Y.F. Chen, Semi-automatic generation of shear wall structural models, Structures 51 (2023) 42每54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.istruc.2023.03.031.

[12] T. Li, B. Shu, X.J. Qiu, Z.Q. Wang, Efficient reconstruction from architectural drawings, International Journal of Computer Applications in Technology 38 (2010) 177每184. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJCAT.2010.034154.

[13] Q. Wen, R.G. Zhu, Automatic generation of 3D building models based on line segment vectorization, Mathematical Problems in Engineering 2020 (2020) e8360706. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/8360706.

[14] L. Gimenez, S. Robert, F. Suard, K. Zreik, Automatic reconstruction of 3D building models from scanned 2D floor plans, Automation in Construction 63 (2016) 48每56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2015.12.008.

[15] M. Urbieta, M. Urbieta, T. Laborde, G. Villarreal, G. Rossi, Generating BIM model from structural and architectural plans using artificial intelligence, Journal of Building Engineering 78 (2023) 107672. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2023.107672.

[16] Z.C. Lin, L.H. Xu, X.S. Xie, Shape function-based multi-objective optimizations of seismic design of buildings with elastoplastic and self-centering components, Computers & Structures 296 (2024) 107303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruc.2024.107303.

[17] Z. Zheng, X.Z. Lu, K.Y. Chen, Y.C. Zhou, J.R. Lin, Pretrained domain-specific language model for natural language processing tasks in the AEC domain, Computers in Industry 142 (2022) 103733. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compind.2022.103733.

[18] Z. Zheng, K.Y. Chen, X.Y. Cao, X.Z. Lu, J.R. Lin, LLM-FuncMapper: Function identification for interpreting complex clauses in building codes via LLM, (2023). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2308.08728.

[19] OpenAI, ChatGPT, (2022). https://openai.com/chatgpt (accessed September 24, 2023).

[20] Google, Bard, (2023). https://bard.google.com (accessed July 20, 2023).

[21] H. Touvron, T. Lavril, G. Izacard, X. Martinet, M.-A. Lachaux, T. Lacroix, B. Rozi豕re, N. Goyal, E. Hambro, F. Azhar, A. Rodriguez, A. Joulin, E. Grave, G. Lample, LLaMA: Open and efficient foundation language models, (2023). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2302.13971.

[22] Z.X. Du, Y.J. Qian, X. Liu, M. Ding, J.Z. Qiu, Z.L. Yang, J. Tang, GLM: General language model pretraining with autoregressive blank infilling, (2022). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2103.10360.

[23] AutoGPT, The official Auto-GPT website, (2023). https://news.agpt.co/ (accessed September 24, 2023).

[24] Y.L. Shen, K.T. Song, X. Tan, D.S. Li, W.M. Lu, Y.T. Zhuang, HuggingGPT: Solving AI tasks with ChatGPT and its friends in Hugging Face, (2023). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2303.17580.

[25] J. Wei, X.Z. Wang, D. Schuurmans, M. Bosma, B. Ichter, F. Xia, E. Chi, Q. Le, D. Zhou, Chain-of-Thought prompting elicits reasoning in large language models, (2023). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2201.11903.

[26] S.Y. Yao, D. Yu, J. Zhao, I. Shafran, T.L. Griffiths, Y. Cao, K. Narasimhan, Tree of Thoughts: Deliberate problem solving with large language models, (2023). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2305.10601.

[27] S.Y. Yao, J. Zhao, D. Yu, N. Du, I. Shafran, K. Narasimhan, Y. Cao, ReAct: Synergizing reasoning and acting in language models, (2023). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2210.03629.

[28] M.H. Li, F.F. Song, B.W. Yu, H.Y. Yu, Z.J. Li, F. Huang, Y.B. Li, API-Bank: A benchmark for tool-augmented LLMs, (2023). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2304.08244.

[29] I. Singh, V. Blukis, A. Mousavian, A. Goyal, D.F. Xu, J. Tremblay, D. Fox, J. Thomason, A. Garg, ProgPrompt: Generating situated robot task plans using large language models, in: 2023 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), 2023: pp. 11523每11530. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICRA48891.2023.10161317.

[30] J. White, Q. Fu, S. Hays, M. Sandborn, C. Olea, H. Gilbert, A. Elnashar, J. Spencer-Smith, D.C. Schmidt, A prompt pattern catalog to enhance prompt engineering with ChatGPT, (2023). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2302.11382.

[31] W.J. Liao, X.Z. Lu, Y.F. Fei, Y. Gu, Y.L. Huang, Generative AI design for building structures, Automation in Construction 157 (2024) 105187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2023.105187.

[32] T.-C. Wang, M.-Y. Liu, J.-Y. Zhu, A. Tao, J. Kautz, B. Catanzaro, High-resolution image synthesis and semantic manipulation with conditional GANs, in: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2018.00917.

[33] S.Z. Qin, W.J. Liao, S.N. Huang, K.G. Hu, Z. Tan, Y. Gao, X.Z. Lu, AIstructure-Copilot: assistant for generative AI-driven intelligent design of building structures, Smart Construction 1 (2024) 0001. https://doi.org/10.55092/sc20240001.

[34] H.P. Lou, Z.B. Xiao, Y.Y. Wan, G. Quan, F.L. Jin, B.Q. Gao, H.J. Lu, Size optimization design of members for shear wall high-rise buildings, Journal of Building Engineering 61 (2022) 105292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2022.105292.

[35] K. Hayashi, M. Ohsaki, Graph-based reinforcement learning for discrete cross-section optimization of planar steel frames, Advanced Engineering Informatics 51 (2022) 101512. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aei.2021.101512.

[36] Ş. Atabay, Cost optimization of three-dimensional beamless reinforced concrete shear-wall systems via genetic algorithm, Expert Systems with Applications 36 (2009) 3555每3561. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2008.02.004.

[37] P. Geyer, Component-oriented decomposition for multidisciplinary design optimization in building design, Advanced Engineering Informatics 23 (2009) 12每31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aei.2008.06.008.

[38] Y.F. Fei, W.J. Liao, X.Z. Lu, E. Taciroglu, H. Guan, Semi-supervised learning method incorporating structural optimization for shear-wall structure design using small and long-tailed datasets, Journal of Building Engineering 79 (2023) 107873. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2023.107873.

[39] Y. Zhang, C. Mueller, Shear wall layout optimization for conceptual design of tall buildings, Engineering Structures 140 (2017) 225每240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engstruct.2017.02.059.

[40] V.J.L. Gan, C.L. Wong, K.T. Tse, J.C.P. Cheng, I.M.C. Lo, C.M. Chan, Parametric modelling and evolutionary optimization for cost-optimal and low-carbon design of high-rise reinforced concrete buildings, Advanced Engineering Informatics 42 (2019) 100962. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aei.2019.100962.

[41] J. MacQueen, Classification and analysis of multivariate observations, in: 5th Berkeley Symp. Math. Statist. Probability, 1967: pp. 281每297.

[42] T. Cali里ski, J. Harabasz, A dendrite method for cluster analysis, Communications in Statistics 3 (1974) 1每27. https://doi.org/10.1080/03610927408827101.

[43] J.H. Yu, Y. Jiang, Z. Wang, Z. Cao, T. Huang, UnitBox: An advanced object detection network, in: Proceedings of the 24th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 2016: pp. 516每520. https://doi.org/10.1145/2964284.2967274.

[44] S.Z. Qin, W.J. Liao, Y.Q. Lin, X.Z. Lu, An efficient assessment method for intelligent design results of shear wall structure based on mechanical performance, material consumption, and empirical rules, Engineering Mechanics (2023). https://doi.org/10.6052/j.issn.1000-4750.2023.05.0360.

[45] Z.H. Zou, Y. Yun, J.N. Sun, Entropy method for determination of weight of evaluating indicators in fuzzy synthetic evaluation for water quality assessment, Journal of Environmental Sciences 18 (2006) 1020每1023. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1001-0742(06)60032-6.

[46] J.H. Holland, Adaptation in natural and artificial systems: An introductory analysis with applications to biology, control and artificial intelligence, The MIT Press, 1992. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/1090.001.0001 (accessed September 27, 2023).

[47] K.A. De Jong, An analysis of the behavior of a class of genetic adaptive systems, Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Michigan, 1975.

[48] YJK Building Software, Y-GAMA, (2024). https://www.yjk.cn/article/836/ (accessed April 23, 2023).

[49] Geatpy development team, Geatpy, (2021). http://geatpy.com/ (accessed May 18, 2024).

[50] H. M邦hlenbein, D. Schlierkamp-Voosen, Predictive Models for the Breeder Genetic Algorithm I. Continuous Parameter Optimization, Evolutionary Computation 1 (1993) 25每49. https://doi.org/10.1162/evco.1993.1.1.25.

[51] Y.F. Fei, W.J. Liao, S. Zhang, P.F. Yin, B. Han, P.J. Zhao, X.Y. Chen, X.Z. Lu, Integrated schematic design method for shear wall structures: A practical application of generative adversarial networks, Buildings 12 (2022) 1295. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings12091295.